| 1794 |

Eli Whitney patents his cotton gin. This invention would lead to the cotton surplus that would eventually increase the availability and lower the cost of wallpaper

|

| 1801 | Karel Dvorak born in Bohemia |

| 1826 | Karel weds Dorota nee Seda |

| 1839 | Dorota births a son, Anton, in Vyhanova, in the Bohemian region of Czechia |

| 1840s | Mechanized roller printing enters the wallpaper market, revolutionizing the practice of printing |

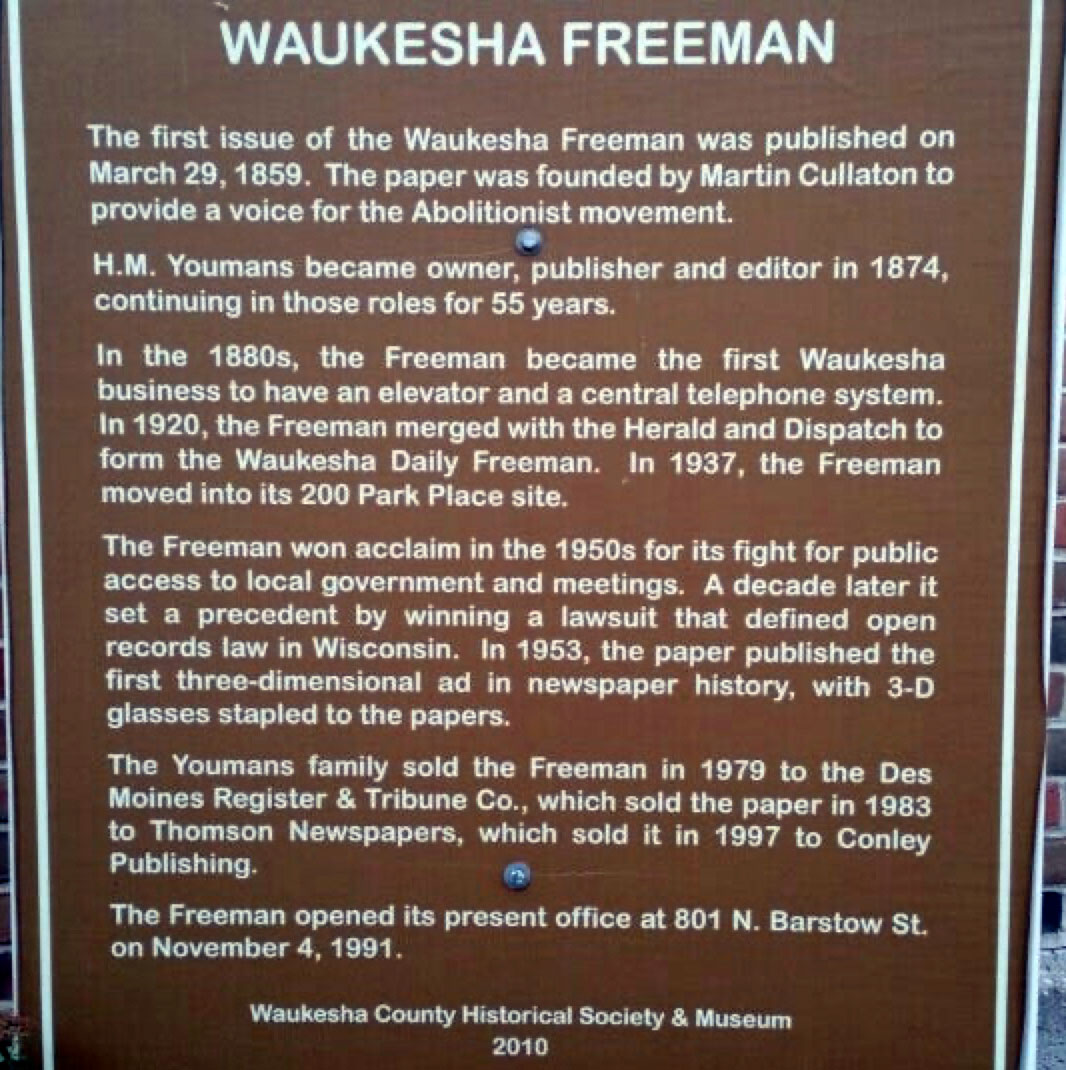

| 1842 | In the United States, C.C. Scholes, the Freeman’s original editor, renames the newspaper from the Milwaukee Democrat to the American Freeman in order to avoid associations with the pro-slavery stance adopted by the Democrat part |

| 1844 | Scholes receives economic support from a coalition centered around Prairieville. As a result, the newspaper is moved to the village; In Philadelphia, the first mechanically printed wallpapers are produced by the Howell & Brother’s firm

|

| 1846 | The issues of the American Freeman pasted in the Dvorak bandbox are printed; Prairieville renamed to Waukesha |

| 1848 | Sherman M. Booth becomes the sole shareholder of the newspaper, renaming it to the Wisconsin Free Democrat and moving it back to Milwaukee. With this, the American Freeman ceases to exist under its former moniker, leaving room for the Waukesha Freeman

|

| 1854 | Glover is broken out of jail. His journey starts in Milwaukee, goes through Waukesha, and ends with his escape to freedom in Canada, all in the same year

|

| 1850-60? | Anton Dvorak moves from Bohemia to the United States, settling in Kane County, Illinois, outside of Chicago. During this period, Anton could have acquired the Dvorak bandbox |

| 1859 |

The Waukesha Freeman, the spiritual successor to the American Freeman, is first published by Martin Cullaton

|

| 1866 |

Anton weds Terezie nee Kvidera in 1866 in Kane County, Illinois

|

| 1869 |

Terezie births a son, Frank, in Illinois

|

| 1890s? |

Frank marries Katherine nee Pribyl

|

| 1900 |

Katherine births a son, Raymond

|

| 1934-1968 |

Raymond moves to Madison, serving as UW's Director of Bands

|